You can find the book at Project Gutenberg:

http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/1684

Here is the chapter you mentioned:

CHAPTER XX

AN AGED AND A GREAT WINE

...

"I am going down to my inner cellar."

"An inner cellar!" exclaimed the doctor.

"Sacred from the butler. It is interdicted to Stoneman. Shall I offer

myself as guide to you? My cellars are worth a visit."

"Cellars are not catacombs. They are, if rightly constructed, rightly

considered, cloisters, where the bottle meditates on joys to bestow, not

on dust misused! Have you anything great?"

"A wine aged ninety."

"Is it associated with your pedigree that you pronounce the age with

such assurance?"

"My grandfather inherited it."

"Your grandfather, Sir Willoughby, had meritorious offspring, not to

speak of generous progenitors. What would have happened had it fallen

into the female line! I shall be glad to accompany you. Port? Hermitage?"

"Port."

"Ah! We are in England!"

"There will just be time," said Sir Willoughby, inducing Dr. Middleton

to step out.

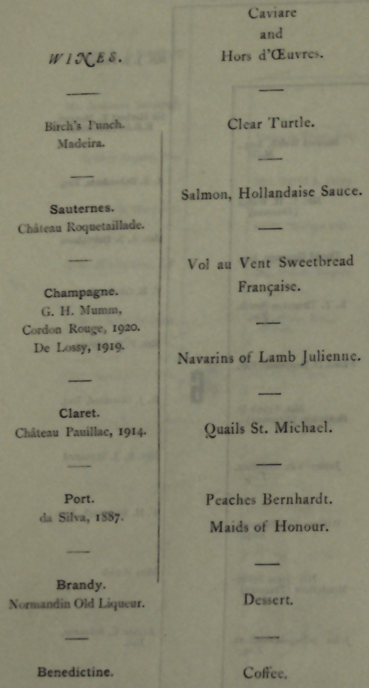

A chirrup was in the reverend doctor's tone: "Hocks, too, have compassed

age. I have tasted senior Hocks. Their flavours are as a brook of many

voices; they have depth also. Senatorial Port! we say. We cannot say

that of any other wine. Port is deep-sea deep. It is in its flavour

deep; mark the difference. It is like a classic tragedy, organic in

conception. An ancient Hermitage has the light of the antique; the merit

that it can grow to an extreme old age; a merit. Neither of Hermitage

nor of Hock can you say that it is the blood of those long years,

retaining the strength of youth with the wisdom of age. To Port for

that! Port is our noblest legacy! Observe, I do not compare the wines; I

distinguish the qualities. Let them live together for our enrichment;

they are not rivals like the Idaean Three. Were they rivals, a fourth

would challenge them. Burgundy has great genius. It does wonders within

its period; it does all except to keep up in the race; it is

short-lived. An aged Burgundy runs with a beardless Port. I cherish the

fancy that Port speaks the sentences of wisdom, Burgundy sings the

inspired Ode. Or put it, that Port is the Homeric hexameter, Burgundy

the pindaric dithyramb. What do you say?"

"The comparison is excellent, sir."

"The distinction, you would remark. Pindar astounds. But his elder

brings us the more sustaining cup. One is a fountain of prodigious

ascent. One is the unsounded purple sea of marching billows."

"A very fine distinction."

"I conceive you to be now commending the similes. They pertain to the

time of the first critics of those poets. Touch the Greeks, and you can

nothing new; all has been said: 'Graiis . . . praeter, laudem nullius

avaris.' Genius dedicated to Fame is immortal. We, sir, dedicate genius

to the cloacaline floods. We do not address the unforgetting gods, but

the popular stomach."

Sir Willoughby was patient. He was about as accordantly coupled with Dr.

Middleton in discourse as a drum duetting with a bass-viol; and when he

struck in he received correction from the paedagogue-instrument. If he

thumped affirmative or negative, he was wrong. However, he knew scholars

to be an unmannered species; and the doctor's learnedness would be a

subject to dilate on.

In the cellar, it was the turn for the drum. Dr. Middleton was

tongue-tied there. Sir Willoughby gave the history of his wine in heads

of chapters; whence it came to the family originally, and how it had

come down to him in the quantity to be seen. "Curiously, my grandfather,

who inherited it, was a water-drinker. My father died early."

"Indeed! Dear me!" the doctor ejaculated in astonishment and condolence.

The former glanced at the contrariety of man, the latter embraced his

melancholy destiny.

He was impressed with respect for the family. This cool vaulted cellar,

and the central square block, or enceinte, where the thick darkness was

not penetrated by the intruding lamp, but rather took it as an eye, bore

witness to forethoughtful practical solidity in the man who had built

the house on such foundations. A house having a great wine stored below

lives in our imaginations as a joyful house, fast and splendidly rooted

in the soil. And imagination has a place for the heir of the house. His

grandfather a water-drinker, his father dying early, present

circumstances to us arguing predestination to an illustrious heirship

and career. Dr Middleton's musings were coloured by the friendly vision

of glasses of the great wine; his mind was festive; it pleased him, and

he chose to indulge in his whimsical, robustious, grandiose-airy style

of thinking: from which the festive mind will sometimes take a certain

print that we cannot obliterate immediately. Expectation is grateful,

you know; in the mood of gratitude we are waxen. And he was a

self-humouring gentleman.

He liked Sir Willoughby's tone in ordering the servant at his heels to

take up "those two bottles": it prescribed, without overdoing it, a

proper amount of caution, and it named an agreeable number.

Watching the man's hand keenly, he said:

"But here is the misfortune of a thing super-excellent: not more than

one in twenty will do it justice."

Sir Willoughby replied: "Very true, sir; and I think we may pass over

the nineteen."

"Women, for example; and most men."

"This wine would be a scaled book to them."

"I believe it would. It would be a grievous waste."

"Vernon is a claret man; and so is Horace De Craye. They are both below

the mark of this wine. They will join the ladies. Perhaps you and I,

sir, might remain together."

"With the utmost good-will on my part."

"I am anxious for your verdict, sir."

"You shall have it, sir, and not out of harmony with the chorus

preceding me, I can predict. Cool, not frigid." Dr. Middleton summed the

attributes of the cellar on quitting it. "North side and South. No musty

damp. A pure air. Everything requisite. One might lie down one's self

and keep sweet here."

Of all our venerable British of the two Isles professing a suckling

attachment to an ancient port-wine, lawyer, doctor, squire, rosy

admiral, city merchant, the classic scholar is he whose blood is most

nuptial to the webbed bottle. The reason must be, that he is full of the

old poets. He has their spirit to sing with, and the best that Time has

done on earth to feed it. He may also perceive a resemblance in the wine

to the studious mind, which is the obverse of our mortality, and throws

off acids and crusty particles in the piling of the years, until it is

fulgent by clarity. Port hymns to his conservatism. It is magical: at

one sip he is off swimming in the purple flood of the ever-youthful antique.

By comparison, then, the enjoyment of others is brutish; they have not

the soul for it; but he is worthy of the wine, as are poets of Beauty.

In truth, these should be severally apportioned to them, scholar and

poet, as his own good thing. Let it be so.

Meanwhile Dr. Middleton sipped.

After the departure of the ladies, Sir Willoughby had practised a

studied curtness upon Vernon and Horace.

"You drink claret," he remarked to them, passing it round. "Port, I

think, Doctor Middleton? The wine before you may serve for a preface. We

shall have your wine in five minutes."

The claret jug empty, Sir Willoughby offered to send for more. De Craye

was languid over the question. Vernon rose from the table.

"We have a bottle of Doctor Middleton's port coming in," Willoughby said

to him.

"Mine, you call it?" cried the doctor.

"It's a royal wine, that won't suffer sharing," said Vernon.

"We'll be with you, if you go into the billiard-room, Vernon."

"I shall hurry my drinking of good wine for no man," said the Rev.

Doctor.

"Horace?"

"I'm beneath it, ephemeral, Willoughby. I am going to the ladies."

Vernon and De Craye retired upon the arrival of the wine; and Dr.

Middleton sipped. He sipped and looked at the owner of it.

"Some thirty dozen?" he said.

"Fifty."

The doctor nodded humbly.

"I shall remember, sir," his host addressed him, "whenever I have the

honour of entertaining you, I am cellarer of that wine."

The Rev. Doctor set down his glass. "You have, sir, in some sense, an

enviable post. It is a responsible one, if that be a blessing. On you it

devolves to retard the day of the last dozen."

"Your opinion of the wine is favourable, sir?"

"I will say this: shallow souls run to rhapsody: I will say, that I am

consoled for not having lived ninety years back, or at any period but

the present, by this one glass of your ancestral wine."

"I am careful of it," Sir Willoughby said, modestly; "still its natural

destination is to those who can appreciate it. You do, sir."

"Still my good friend, still! It is a charge; it is a possession, but

part in trusteeship. Though we cannot declare it an entailed estate, our

consciences are in some sort pledged that it shall be a succession not

too considerably diminished."

"You will not object to drink it, sir, to the health of your

grandchildren. And may you live to toast them in it on their marriage-day!"

"You colour the idea of a prolonged existence in seductive hues. Ha!

It is a wine for Tithonus. This wine would speed him to the rosy

Morning aha!"

"I will undertake to sit you through it up to morning," said Sir

Willoughby, innocent of the Bacchic nuptiality of the allusion.

Dr Middleton eyed the decanter. There is a grief in gladness, for a

premonition of our mortal state. The amount of wine in the decanter did

not promise to sustain the starry roof of night and greet the dawn. "Old

wine, my friend, denies us the full bottle!"

"Another bottle is to follow."

"No!"

"It is ordered."

"I protest."

"It is uncorked."

"I entreat."

"It is decanted."

"I submit. But, mark, it must be honest partnership. You are my worthy

host, sir, on that stipulation. Note the superiority of wine over

Venus! I may say, the magnanimity of wine; our jealousy turns on him

that will not share! But the corks, Willoughby. The corks excite my

amazement."

"The corking is examined at regular intervals. I remember the occurrence

in my father's time. I have seen to it once."

"It must be perilous as an operation for tracheotomy; which I should

assume it to resemble in surgical skill and firmness of hand, not to

mention the imminent gasp of the patient."